Sherlock Holmes making deductions in his mind palace about John Chrystostom

Historical research is punctuated by mysteries great and small. I solved a micro-mystery today. It was The Case of the Dubious Reference, or The Mystery of the Golden Mouth. “Golden Mouth” (Chrysostomos, Greek: ὁ Χρυσόστομος) was a title given to the preacher and Bishop by the name of John (St. John Chrysostom, c. 349-407) who preached in Antioch and was consecrated Archbishop of Constantinople. He was called “the golden mouth” because of his gift for preaching. Centuries earlier, a Greek philosopher and orator had also been honored with that title, Dio Chrysostom.

John Calvin often cites John Chrysostom, both positively and negatively. When it came to biblical interpretation, Chrysostom was one of his favorites, because his exegesis tended to be more literal than some other church fathers who preferred to find allegories all through the biblical text. But Calvin was rather unhappy with Chrysostom’s theology of grace and human free will. Chrysostom frequently emphasizes human efforts and virtue in salvation and asserts that grace has to be merited, and that salvation is a cooperative effort between God and sinners. This was not uncommon in the early church, before the controversy between Augustine and Pelagius. By contrast, Calvin was quite critical of Augustine’s exegesis, because he was quite prone to this kind of spiritual interpretation, which Calvin found fanciful and speculative, particularly because medieval Roman Catholic theology used this kind of spiritual exegesis to justify doctrines that the Reformers rejected. But Augustine was Calvin’s favorite when it came to the doctrines of grace, the bondage of the will to sin, and a divine predestination not based on foreseen merit.

Now for the mystery. Calvin cites Chrysostom several times in his Institutes of the Christian Religion, 2.2.4, when he is talking about the capacities of the human will after humanity’s fall into sin. These references originated in the second Latin revision of the Institutes from 1539. This is a topic on which he thinks Chrysostom is quite wrong, and it’s not just because he doesn’t understand Chrysostom’s homiletical context.[note] Pace an otherwise interesting article by György Papp, “Aspects of Calvin’s use of Chrysostom-Quotations Concerning the Free Will,” in Herman J. Selderhuis and Arnold Huijgen, eds., Calvinus Pastor Ecclesiae: Papers of the Eleventh International Congress on Calvin Research (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2016), 423-433). Papp underestimates Chrysostom’s emphasis on human striving, effort, and virtue, and he does not take into account the fact that rejecting late medieval semi-Pelagianism was a central doctrinal concern of the Reformation. [/note] Calvin cites three statements from Chrysostom’s Homiliae in Genesim (Homilies in Genesis) and gives references for the first and third of these citations.[note]Opera Selecta 3: 245, McNeill-Battles ed., 1: 259.[/note] Footnoting was random and capricious in those wicked and dark days of the sixteenth century. The editors of the Opera Selecta (Karl Barth’s brother Peter and two other Barthian scholars, Wilhelm Niesel and Dora Scheuner) identify the second reference as In Gen. hom. 25.7. This is wrong.

The first clue that this is a mistake is that Calvin introduces the next citation with the words “Dixerat autem prius,” “He had previously said”–Autem here is basically a comma; ignore it–and then Calvin cites a passage from In Gen. hom. 53.2. So one would expect that the previous citation would occur after that sentence in homily 53.2. I don’t blame the editors; it can be exceptionally hard to figure out Calvin’s references, and he is prone to mistakes in citations, particularly biblical citations. But still, I am surprised that they did not look for something that occurs after the third citation.

One of the difficulties is that there are a number of Latin translations of Chrysostom that are and were available. Calvin’s Latin does not appear verbatim in the Latin translation that was included in the 19th-century edition thrown together by J-P Migne, the Patrologia Graeca. But Calvin can also paraphrase a passage or alter it to fit the grammar and syntax of his writing. Calvin’s citation or paraphrase reads: Item, Sicut nisi gratia Dei adiuti, nihil unquam possumus recte agere: ita nisi quod nostrum est attulerimus, non poterimus supernum acquirere favorem. (“Further, he says that, just as we cannot ever do anything correctly apart from the grace of God, in the same way, unless we bring what is our own, we will not be able to obtain favor from above.”) You will not find those exact words in the Patrologia Graeca.

Nevertheless, I persisted.

Because you have to be somewhat obsessive in this field. Just enough to enable you to make discoveries, but just short of needing to be institutionalized.

I searched Chrysostom’s homilies on Genesis for something that sounded similar, and which occurred after homily 53, section 2. Fortunately, I found something rather similar at the very end of homily 58, except that it refers to obtaining God’s help rather than his favor.[note]Sicut enim nisi illo subsidio fruamur, nihil umquam possumus recte agere: ita nisi quod nostrum est attulerimus, non poterimus auxilium obtinere. [/note] This could be a simple matter of a different translation, however.

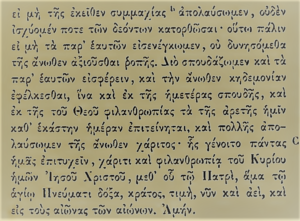

Greek text in de Montfaucon’s edition

I checked the passage in the 19th-century edition of Calvin’s works that the Opera Selecta editors used, edited by Bernard de Montfaucon (1655-1741) who invented the science of paleography. in the process I learned that the Latin translation in de Montfaucon’s edition is the one “borrowed” by the prolific plagiarist Jacques-Paul Migne’s Patrologia Graeca.[note]See Sancti patris nostri Joannis Chrysostomi opera omnia quae exstant, ed. Bernard de Montfaucon, 13 vols. (Paris: Gaume Fratres, 1834-1838), 4: 658-659; Migne, Patrologia Graeca 54: 513. [/note]

But there was more. During my investigations, I ran across some fascinating recent work by Drs. Jeannette Kreijkes on Calvin’s use of Chrysostom. She is writing a dissertation on this topic at the University of Groningen. She has refuted the common assumption that Calvin only used one edition of Chrysostom’s works, the Latin translation published in Paris in 1536 by Claude Chevallon, which does not include Chrysostom’s Greek.[note]Jeannette Kreijkes, “Calvin’s Use of the Chevallon Edition of Chrysostom’s Opera Omnia: The Relationship between the Marked Sections and Calvin’s Writings,” Church History and Religious Culture 96.3 (2016): 237–265. She refutes some of the main arguments in Alexandre Ganoczy and Klaus Müller, Calvins handschriftliche Annotationen zu Chrysostomus: Ein Beitrag zur Hermeneutik Calvins (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1981), and in W. Ian P. Hazlett, “Calvin’s Latin Preface to his Proposed French Edition of Chrysostom’s Homilies: Translation and Commentary,” in. James Kirk, ed., Humanism and Reform: The Church in Europe, England, and Scotland, 1400-1643 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 129-150.[/note] I had a very good conversation with her as well, and I learned from her something about the various editions that were available during Calvin’s day. She also has access to the 1536 Chevallon edition, which is nowhere online and quite hard to find. How does Chevallon’s translation of the passage read?

Eureka!

Chevallon’s edition is much closer to Calvin’s citation, and in fact, the latter part is identical.[note]“Sicut autem nisi illam habeamus, nihil unquam possumus recte agere possumus, nisi superna gratia adiuti. Sicut autem nisi illam habeamus, nihil unquam possumus recte agere: ita nisi quod nostrum attulerimus, non poterimus supernum acquirere favorem.” Divi Ioannis Chrysostomi Archiepiscopi Constantinopolitani Opera, 5 vols. (Paris: Claude Chevallon, 1536), 1: fol. 118 vo. [/note] Does this prove that Calvin was using the Chevallon edition? Not at all.

Johannes Oecolampadius and his rather square beard.

Some scholars tend to assume that Calvin used the Chevallon edition throughout his career. When I first found that the Chevallon edition corresponded to Calvin’s citation, that was my first thought as well. But the Chevallon edition is identical in this passage to the translations found in editions prepared by Oecolampadius [note]Divi Ioannis Chrysostomi… in totum Geneseos librum Homiliae, trans. Johannes Oecolampadius (Basel: A. Cratander, 1523), fol. 169 vo .[/note] in 1523 and Erasmus[note] D. Ioannis Chrysostomi archiepiscopi Constantinopolitani opera quae hactenus versa sunt omnia, etc. ed. Desiderius Erasmus, 5 vols. (Basel: Froben, 1530), 5: 307. [/note] in 1530.

But I think it was Oecolampadius. Why? Because immediately afterward, Calvin cites Chrystostom’s Genesis homilies again, this time In Gen. hom. 53.2. [note]Patrologia Graeca 54: 466).[/note] Except that Calvin’s marginal reference does not indicate homily 53, but homily 52. And the homily that the other editions number as 53, Oecolampadius numbers as 52, because, for some reason, he omits the first homily that the others include and enumerate as homily 1. But that’s a mystery for another day. It is possible that there was another edition that numbered the homilies the same way that I have not found, or that Calvin simply made an error, but my detective instincts do not lean that way. For now, I think Oecolampadius is the prime suspect, and at the very least he should be handcuffed, read his rights, and hauled down to the station for further questioning.

Solving these little micro-mysteries is very satisfying; who doesn’t enjoy a good mystery? (My favorite mystery writer is Lyndsay Faye, whose mysteries are set in the 19th century). And along the way, I met a fellow historical detective, Jeannette Kreijkes, who is a formidable Calvin scholar, to whom I owe much of what I found and learned on this case.