John Balyo, a former radio host for the local Christian station WCSG, has been arrested for sexually abusing a child, and allegedly admits to at least some of the accusations. This gave rise to a question by one of my pastoral colleagues in a closed forum. The gist of the question was: Does the church bear some responsibility for this, because we do not provide a place for sinners to openly confess their sins and struggles? If we lack of a venue to talk about temptations in a safe environment, a place to hold each other accountable and in which to find forgiveness and healing, does this lead to heinous sins such as child molestation?

It was a valuable question, but a complicated one.

It’s complicated by the nature of the case used as an example. The question also went sideways when we got into a debate about whether all sins are the same.

On that last question, there is one and only one sense in which all sins are the same. All sins make a person a sinner. Any sin, and even the condition of original sin, leave each one of us guilty before God and in need of forgiveness and salvation. The bad news is that everyone is equally a sinner; the good news is that God in Christ extends forgiveness for every variety of sinner. He stands ready to forgive all sins (save one). This was the point that the Pharisees tended to forget. Jesus needed to remind them that just because they did not poison the guy next door and hide the body, they still harbored hateful thoughts against him in secret. This mental malice, Jesus says, is also a species of murder, and a violation of the sixth commandment. It also counts as a failure to love one’s neighbor as oneself. This sameness of all sins is what the vast majority of Christians (in my experience) emphasize the vast majority of the time. The intentions are good, even godly. We want to hold out the promise of forgiveness and healing to everyone without exception, even perpetrators of abuse. The tendency to equate all sins may also be a reaction to the old tradition of shaming people for public transgressions, particularly the sin of adultery. There was a day when a couple that got pregnant before marriage would have to publically confess their intimate moral failure before the congregation. Making all sins equal may also be a reaction against harsh attitudes homosexual behavior (or even orientation). But like all pendulum swings, it is an over-reaction.

Apart from Jesus’ important correction to the Pharisees, the sameness of all transgressions is not the dominant emphasis in the Bible. In light of biblical teaching about sin, I think it is a serious mistake to default to the position that “all sins are the same,” despite the fact that it does seem to be the default position among average believers nowadays. Not all sins are of equal weight, not even in God’s eyes. Jesus declared that Herod was “guilty of a greater sin” than Pilate who stood in judgment over Jesus. Herod was a Jew (at least in name) and should have known better. There is the “sin against the Holy Spirit,” which Jesus says is unforgivable. Paul makes it clear to the Corinthian church that sexual transgressions are worse than other sins, I Corinthians 6:18. The intimate joining of bodies in sex also joins souls; to join them casually, with no strings attached, as friends with benefits, scars the soul. This stands in contrast to our culture’s minimizing of the life-creating and soul-binding potential of sex which has the potential for profound beauty and profound harm. There is no such thing as casual sex. Paul declares that another sexual sin to which the Corinthians were turning a blind eye (a man having an affair with his step-mother) was much worse than the sins commonly seen among their pagan neighbors (I Corinthians 5). The apostle’s strong rebuke of the Corinthians for their tolerance of this sin is based in the fact that this particularly vile offense harms the reputation of Christ’s church, and thus harms the cause of the gospel. The Corinthian church itself was committing a sin by standing by and doing nothing, sending the message that this behavior is acceptable to followers of Christ. And in words that might shock our modern nonjudgmental sensibilities, Paul says that it is our duty to judge those who are members of the church. In many practical ways, all sins are not the same. All sins do not bring about the same degree of destructive consequences. Not every transgression is as intentional as another. Some sins arise more out of weakness than malice.

The problem with defaulting to “all sins are the same” is that it minimizes the destructive power of our choices. For example, a person who decides not only to have an affair, but also to abandon their spouse and children and pursue the illicit relationship, can easily tell themselves that these choices are no more sinful than wishing you had your neighbor’s new car rather than the old clunker you drive to work every day. All I have to do is ask forgiveness and move on with my new life with my new partner and my children will be happier because I am happier. And believe me, people do rationalize and minimize their sin this way, and our simplistic Christian clichés can contribute to this casual attitude toward sin.

But getting back to the original question: Is the church to blame when pedophiles act on their impulses? I think the answer is no, even though I can agree that churches do not always create or foster adequate and effective opportunities for our members to practice mutual confession and accountability. I don’t think most persons who have a compulsive drive to abuse children would open up about these impulses if only they had a small group where they felt free and safe to confess their deepest, darkest desires. And so using the Christian radio DJ as an example, pedophilia as an example, inevitably makes the question about how the church ministers to sinners go sideways. In my very real and all-too-painful experience, the tragedy is not that churches take this kind of sin against children too seriously, but that they naïvely treat it just like any other sin. Pedophilia is not like any other sin. It is an enslaving, enduring compulsion. You cannot simply forgive and forget child sexual abuse. You can forgive (if in fact you are a victim of it; one cannot forgive a sin committed against someone else); but you must not forget. For the sake of the children in the congregation, you may not forget, and even for the sake of the offender, you may not forget. To forget is to invite your own culpability in the future abuse of a child. Pedophilia is not a passing phase. It is not a sin like any other sin, and it is exceptionally unhelpful to suggest that other sins like using pornography can lead just about anyone to become a child sexual predator, as this post may or may not imply (I don’t know the author’s intention, but some people read it that way, and it’s not hard to see why.) Pedophilia is typically a lifelong compulsion, a form of bondage, with which a person may struggle to their dying day—even for those who put their faith in Christ and who seek forgiveness and reconciliation. In addition, manipulation is a major part of how child sexual offenders gain access to their victims. Child sexual predators can be extremely convincing, because they have learned to be emotionally manipulative in order to gain access to their victims and to prepare (“groom”) them for abuse. And the harsh reality is this: those who prey on children will sometimes use the goodwill of decent people, including church members, in order to gain access to potential victims. Many offenders were victims of abuse themselves, but it is the nature of this compulsion that the predator will often use that fact to gain sympathy and to secure the too-easy forgiving and forgetting of persons who do not understand the nature of this sin. But we do not do the offender any favors by minimizing his or her sin, and making it the same as speeding on the highway. Worse, we put children at risk when we don’t take it seriously. The person trapped in this harmful compulsion needs grace and healing, but we can help such persons without putting children and the vulnerable in harm’s way.

Sometimes we even blame the victim. We then become complicit in the abuse; we re-abuse the victim. Please understand this: When an adult has sexual contact with a minor, it is not the minor’s fault. I have heard Christian people say, “Well, she was troubled, she was promiscuous, so it’s not all his fault. She’s partly to blame.” Yes, it is all his fault. No, she is not partly to blame. Especially if she was troubled, if she was promiscuous. The perpetrator is entirely at fault because that adult person intentionally took advantage of a child or teen who was hurting and vulnerable. That’s what sexual predators do. They have a kind of radar that can sense this vulnerability, and that’s when they start grooming their victims for abuse. The Christian community, particularly in its most conservative manifestations, often gets this terribly wrong, sometimes even blaming the victims of abuse, as this article points out. This is why it is so important that we have a Safe Church Ministry in our denomination, and why we should listen to their advice (which is forged from experience) when it comes to doing all that we can to create safe environment in our churches.

Using the radio DJ as an example made the question go sideways, but it is still a very important question. Do we create safe places for our members to experience true, transformative community? When I was administering the biblical-theological examination for Dr. Suzanne McDonald at the last meeting of our Classis, she made excellent observation that young adults are hungering for community. I think perhaps we all are. That’s why I find what Josiah Gorter and his companions are doing at The Grace House in Sacramento so interesting. But what can we do here in our corner of Gaines and Byron Townships to create a place where people can forge relationships that are more than casual acquaintances?

God calls the church to be a hospital for sinners. I can’t imagine anyone disagrees with that. But an obstacle we face is that we don’t seem to have the opportunity—we don’t have the mechanism, or a spiritual practice—by which we can open up to each other about our sins and find forgiveness and healing (James 5:16), a place where we can share our burdens and help each other carry those burdens (Galatians 6:1-2). In order to do this, we have to forge relationships that go deeper than the superficial, and that is exceedingly difficult in a culture where we isolate ourselves from each other in suburban homes, where we live in a “development” that is not quite a neighborhood in the fullest sense of the term, where we drive to and from work alone, daily appearing and disappearing behind an automatic garage door. That, to me, is the hard question. I have seen a few examples of congregations in which these relationships were fostered, in mentoring relationships, or in small groups. It can be done. The real question may be: are we willing to take the risk of being vulnerable? And will we find someone who is willing to take on, as a ministry, the work of creating these opportunities for mentoring and small group fellowship and accountability? Will we see it as just adding one more thing to our busy lives? Or would it be the one thing that we add that puts the rest of our lives into perspective? Would it be the one commitment by which we can really hear God speaking to us by his Spirit, where we can concretely feel the grace of Christ expressed in the people who together form his Body? I know that we can, because we can do all things through Christ who gives us strength. I cannot do it all myself, because I am not the Christ, and I am not the church. Nor am I exactly sure about how to do it, beyond my sense that perhaps a very intentional small group ministry would help us in the life of discipleship. Perhaps there are also other ways to meet this need; maybe some creative ideas will come from our members, or from other church leaders in our area. But I know we can do it, together, with God’s help.

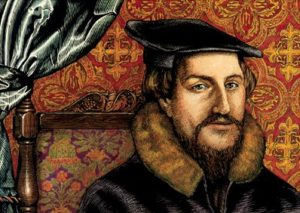

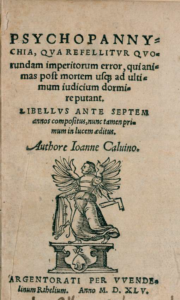

This experience of exile from France, his homeland, and from the Roman Catholic form of the faith, the faith of his childhood—both of which must have been traumatic—comes out in his first theological writing,

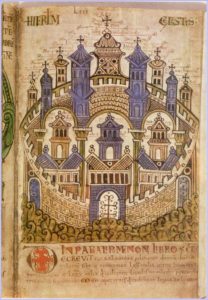

This experience of exile from France, his homeland, and from the Roman Catholic form of the faith, the faith of his childhood—both of which must have been traumatic—comes out in his first theological writing,  Looking ahead to being in the presence of his Savior after this life, Calvin compares it to the Israelites entering the promised land, and the holy city of Jerusalem. In this, Calvin reflects the tradition of Christian spirituality that sees Jerusalem as the symbol of unhindered fellowship with God, as depicted in Revelation 21:10.

Looking ahead to being in the presence of his Savior after this life, Calvin compares it to the Israelites entering the promised land, and the holy city of Jerusalem. In this, Calvin reflects the tradition of Christian spirituality that sees Jerusalem as the symbol of unhindered fellowship with God, as depicted in Revelation 21:10. But it’s very important to note that the traditional, Christian view of pilgrimage is not a journey of self-discovery. Nor is it a search for an unknown God. Nor is it a solitary, self-focused enterprise; there are companions on the journey. Fleming Rutledge brought up this potential objection with me when I was posting about the topic of spiritual pilgrimage in connection with

But it’s very important to note that the traditional, Christian view of pilgrimage is not a journey of self-discovery. Nor is it a search for an unknown God. Nor is it a solitary, self-focused enterprise; there are companions on the journey. Fleming Rutledge brought up this potential objection with me when I was posting about the topic of spiritual pilgrimage in connection with  In his day, Calvin repudiated the practice of pilgrimages as a means to earn merit by one’s own exertions. But the biblical theme of the Christian life or the life of the church as a pilgrimage is dear to him, just as it was to many throughout the history of Christian thought. Not a pilgrimage of self-discovery. Not a pilgrimage to accrue merits. Not a pilgrimage to make oneself worthy. It is the journey through this world, this life, to our true home, and to our Lord, who made the pilgrimage from heaven to earth to be our Savior. As such, the Christian life is not a pilgrimage of works, but a pilgrimage of grace. Not a journey of self-justification, but of the Spirit’s sanctification.

In his day, Calvin repudiated the practice of pilgrimages as a means to earn merit by one’s own exertions. But the biblical theme of the Christian life or the life of the church as a pilgrimage is dear to him, just as it was to many throughout the history of Christian thought. Not a pilgrimage of self-discovery. Not a pilgrimage to accrue merits. Not a pilgrimage to make oneself worthy. It is the journey through this world, this life, to our true home, and to our Lord, who made the pilgrimage from heaven to earth to be our Savior. As such, the Christian life is not a pilgrimage of works, but a pilgrimage of grace. Not a journey of self-justification, but of the Spirit’s sanctification. As I work on a new translation of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion, the image of pilgrimage and its related themes show up frequently. So, for example, Calvin interprets the Old Testament promises to Abraham as ultimately pointing to the New Jerusalem:

As I work on a new translation of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion, the image of pilgrimage and its related themes show up frequently. So, for example, Calvin interprets the Old Testament promises to Abraham as ultimately pointing to the New Jerusalem: