Calvin’s Self-Identity as Pilgrim

John Calvin, born Jean Cauvin, was a Frenchman who spent most of his life outside of France. He was forced to flee his native country because of his involvement with the rebellion against the Roman Catholic church, the Reformation. Scholars have commented on how Calvin’s experience as an exile, as a refugee, shaped him as a theologian and pastor. And as an exile and refugee, Calvin embraced the age-old Christian image of the Christian life as a pilgrimage.

John Calvin, born Jean Cauvin, was a Frenchman who spent most of his life outside of France. He was forced to flee his native country because of his involvement with the rebellion against the Roman Catholic church, the Reformation. Scholars have commented on how Calvin’s experience as an exile, as a refugee, shaped him as a theologian and pastor. And as an exile and refugee, Calvin embraced the age-old Christian image of the Christian life as a pilgrimage.

Bruce Gordon, in his excellent biography of Calvin, writes about how this experience of exile was formative for Calvin.

From his earliest Christian writings the young Frenchman described the Christian life with metaphors of journeying and pilgrimage. The imagery was as old as the ancient books of the Hebrew Bible, but Calvin’s brilliance lay in his ability to infuse old traditions with new life. Conversion, he believed, was the beginning point of a journey, not its conclusion. Whether speaking in terms of mental anguish or of sudden conversion he sought to explain how God had acted to change his life and put him on a new course, to send him out in a different direction.

BRUCE GORDON, CALVIN, 34

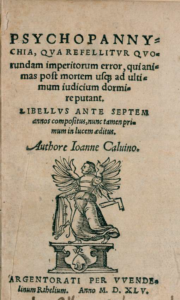

This experience of exile from France, his homeland, and from the Roman Catholic form of the faith, the faith of his childhood—both of which must have been traumatic—comes out in his first theological writing, Psychopannychia. The title, loosely translated, means “soul sleep,” and refers to the doctrine that the soul dies with the body and is resurrected at death. It was taught by the Avignon Pope John XXII and later condemned as a heresy. In Calvin’s day, the doctrine was revived by some Anabaptists, but also, more importantly, by Michael Servetus, who also denied the doctrine of the Trinity. Calvin wrote this treatise in 1534, but did not publish it right away, instead publishing his summary of the Protestant faith, The Institutes of the Christian Religion. For Calvin, the pilgrimage that is the Christian life ends with the vision of God, even before the resurrection of the body at the last day. This is not a novel or unusual doctrine; it was also the teaching of the church catholic, with only occasional exceptions, such as in the case of Pope John XXII. To deny that, Calvin believed, was to deny the clear teaching of Scripture and to deny the true Christian hope.

This experience of exile from France, his homeland, and from the Roman Catholic form of the faith, the faith of his childhood—both of which must have been traumatic—comes out in his first theological writing, Psychopannychia. The title, loosely translated, means “soul sleep,” and refers to the doctrine that the soul dies with the body and is resurrected at death. It was taught by the Avignon Pope John XXII and later condemned as a heresy. In Calvin’s day, the doctrine was revived by some Anabaptists, but also, more importantly, by Michael Servetus, who also denied the doctrine of the Trinity. Calvin wrote this treatise in 1534, but did not publish it right away, instead publishing his summary of the Protestant faith, The Institutes of the Christian Religion. For Calvin, the pilgrimage that is the Christian life ends with the vision of God, even before the resurrection of the body at the last day. This is not a novel or unusual doctrine; it was also the teaching of the church catholic, with only occasional exceptions, such as in the case of Pope John XXII. To deny that, Calvin believed, was to deny the clear teaching of Scripture and to deny the true Christian hope.

Again, Gordon writes about Calvin’s Psychopannychia:

In this meditation on the Bible Calvin set out a theme that he would continue to develop throughout his life—the Christian life as a pilgrimage through the world towards eternity.

BRUCE GORDON, CALVIN, 44

Calvin looked to the passage in Hebrews 11:8-12 where Abraham receives the promises of God and, exiled from his homeland of Ur, lives as a pilgrim and wayfarer, never seeing the fulfillment of the promises the Lord made to him. Calvin writes in Psychopannychia:

The Apostle speaks of Abraham and his descendants who inhabited a foreign land among strangers, not only as exiles, certainly as aliens, barely keeping a roof over their bodies in lowly shanties. This was in obedience to God’s command that he gave to Abraham, that he should leave his land and his relations. God had promised them what he had not yet shown them. Therefore, they welcomed the promises from a distance and died in the confident faith that one day God would make good on his promises. In keeping with that faith, they confessed that they had no permanent residence on the earth and that there was a homeland for them beyond the earth that they longed for, namely, in heaven.

CALVIN, PSYCHOPANNYCHIA, CO 5:218 (MY TRANSLATION)

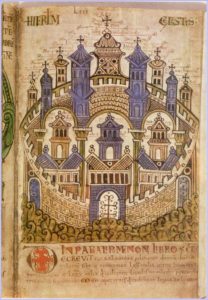

Looking ahead to being in the presence of his Savior after this life, Calvin compares it to the Israelites entering the promised land, and the holy city of Jerusalem. In this, Calvin reflects the tradition of Christian spirituality that sees Jerusalem as the symbol of unhindered fellowship with God, as depicted in Revelation 21:10.

Looking ahead to being in the presence of his Savior after this life, Calvin compares it to the Israelites entering the promised land, and the holy city of Jerusalem. In this, Calvin reflects the tradition of Christian spirituality that sees Jerusalem as the symbol of unhindered fellowship with God, as depicted in Revelation 21:10.

Thus, the souls of the saints, which have escaped the hands of the enemy, are at peace after death. They exist in sumptuousness, of which it is said, “They will go from abundance to abundance.” But when the Heavenly Jerusalem has risen up in her glory, and Christ, the true Solomon, the Prince of Peace, sits in his exalted judgment seat, the true Israelites will reign with their king.

CALVIN, PSYCHOPANNYCHIA, CO 5:214 (MY TRANSLATION)

But it’s very important to note that the traditional, Christian view of pilgrimage is not a journey of self-discovery. Nor is it a search for an unknown God. Nor is it a solitary, self-focused enterprise; there are companions on the journey. Fleming Rutledge brought up this potential objection with me when I was posting about the topic of spiritual pilgrimage in connection with Lisa Deam’s beautiful new book, 3000 Miles to Jesus. The warning is well-taken, given the individualistic focus of modern Western spirituality and its tendency to create one’s own reality and to focus on our own achievements rather than on what God has done for us. 3000 Miles to Jesus describes a very different activity, one centered on Christ and what he has already done for us. She addresses this head-on:

But it’s very important to note that the traditional, Christian view of pilgrimage is not a journey of self-discovery. Nor is it a search for an unknown God. Nor is it a solitary, self-focused enterprise; there are companions on the journey. Fleming Rutledge brought up this potential objection with me when I was posting about the topic of spiritual pilgrimage in connection with Lisa Deam’s beautiful new book, 3000 Miles to Jesus. The warning is well-taken, given the individualistic focus of modern Western spirituality and its tendency to create one’s own reality and to focus on our own achievements rather than on what God has done for us. 3000 Miles to Jesus describes a very different activity, one centered on Christ and what he has already done for us. She addresses this head-on:

Focusing on our destination sounds distinctly countercultural today. Often, when it comes to pilgrimage, we hear sayings like “It’s the journey that matters” or “The search is the meaning.” Yet this viewpoint would have been unimaginable for medieval pilgrims. Sometimes we forget that, historically, a pilgrimage almost always had an endpoint. The pilgrim arrived! The goal was attained! The journey was completed! Yes, the act of travel might itself have been transformational, but it led pilgrims to a single destination the way a well-shot arrow hits its mark.

LISA DEAM, 3000 MILES TO JESUS, 35

Rutledge pointed out that what is most important is Jesus’ journey to us. Indeed it is, and Lisa Deam writes about just that fact, that Jesus came to us to draw us to himself:

But how will the pilgrim get there? How will she survive the turbulent waters? How will any of us? “So that we might also have the means to go,” writes Augustine, “the one we were longing to go to came here from there. And what did he make? A wooden raft for us to cross the sea on.” A raft might seem a bit rickety for the raging sea, but Augustine explains: “For no one can cross the sea of this world unless carried over it on the cross of Christ.”

LISA DEAM, 3000 MILES TO JESUS, 110-111

In his day, Calvin repudiated the practice of pilgrimages as a means to earn merit by one’s own exertions. But the biblical theme of the Christian life or the life of the church as a pilgrimage is dear to him, just as it was to many throughout the history of Christian thought. Not a pilgrimage of self-discovery. Not a pilgrimage to accrue merits. Not a pilgrimage to make oneself worthy. It is the journey through this world, this life, to our true home, and to our Lord, who made the pilgrimage from heaven to earth to be our Savior. As such, the Christian life is not a pilgrimage of works, but a pilgrimage of grace. Not a journey of self-justification, but of the Spirit’s sanctification.

In his day, Calvin repudiated the practice of pilgrimages as a means to earn merit by one’s own exertions. But the biblical theme of the Christian life or the life of the church as a pilgrimage is dear to him, just as it was to many throughout the history of Christian thought. Not a pilgrimage of self-discovery. Not a pilgrimage to accrue merits. Not a pilgrimage to make oneself worthy. It is the journey through this world, this life, to our true home, and to our Lord, who made the pilgrimage from heaven to earth to be our Savior. As such, the Christian life is not a pilgrimage of works, but a pilgrimage of grace. Not a journey of self-justification, but of the Spirit’s sanctification.

Along the way, we have practices to help us on this lifelong trek. Lisa Deam writes of the practice of prayer, for example:

“For prayer is its own pilgrimage and a mountainous way. It transforms us into travelers who walk a steep and winding path. When we pause to pray or meditate, we leave behind our surroundings in the outer world, with its unceasing clamor, and journey to what Saint Bonaventure called the interior Jerusalem—that place deep within where Jesus awaits. In its own way, the inner road to Jerusalem is as demanding as the physical quest of the Alps.”

LISA DEAM, 3000 MILES TO JESUS, 80

Pilgrimage in Calvin’s Institutes

As I work on a new translation of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion, the image of pilgrimage and its related themes show up frequently. So, for example, Calvin interprets the Old Testament promises to Abraham as ultimately pointing to the New Jerusalem:

As I work on a new translation of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion, the image of pilgrimage and its related themes show up frequently. So, for example, Calvin interprets the Old Testament promises to Abraham as ultimately pointing to the New Jerusalem:

We see that all these things [the promises to the patriarchs] do not properly apply to the land of our pilgrimage, or to the earthly Jerusalem, but to the true homeland of the faithful and that heavenly city in which the Lord has decreed blessing and life forever.

CALVIN, INSTITUTES, 2.11.2

The Holy Spirit sustains us in our journey, one in which we might feel like “the walking dead,” spiritual zombies, so to speak:

For the same reason [the Spirit] is called “the pledge and seal” of our inheritance (2 Cor. 1:22) because, as we are making pilgrimage in the world and are like dead people, from heaven he makes us alive in such a way that we are certain that our salvation is secure in God’s dependable protection.

CALVIN, INSTITUTES, 3.1.3

We can get distracted from our destination, tempted to take a permanent detour to enjoy pleasures and diversions along the way. But Calvin urges us to meditate on that future life, to stay focused on the goal:

On the contrary, Christ teaches us to continue as pilgrims in the world so that we will not lose or be deprived of our heavenly inheritance.

CALVIN, INSTITUTES, 3.7.3

We can use and enjoy God’s early gifts, but we are also called to recognize that we do not live for these things; they are provisions for the journey:

Through his Word, the Lord prescribes this measure [for the use of earthly goods] when he teaches that the present life is like a pilgrimage for his people in which they are making their way toward the heavenly kingdom.

CALVIN, INSTITUTES, 3.10.1

Contrary to the late medieval idea of striving to become deserving and anxiously trying to accrue merit with God, Calvin describes the Christian life as a pilgrimage of sanctification. It arises out of gratitude for the justification we have received in Christ.

In the same way, if we have died with Christ (as suits his members) we must seek the things that are above and be pilgrims in the world, that we may aspire to heaven where our treasure is.

CALVIN, INSTITUTES, 3.16.2

The journey is not one of drudgery, Calvin says, but one in which we experience joy because of our salvation in Christ:

The sole and perfect happiness is known to us—even in this earthly pilgrimage. But this happiness sets our hearts afire more and more each day to desire it until it satisfies us with its full fruition.

CALVIN, INSTITUTES, 3.25.2

Finally, Calvin rejects asceticism, and he thinks it an act of ingratitude to reject what he sees as the Lord’s gifts, his supplies, provisions, and aids for the journey. He numbers the civil government among these gifts, and so he denies the teaching of the Anabaptists that the civil government is irredeemable and to be repudiated by Christians:

But if it is the will of God that we make pilgrimage upon the earth while we aspire to our true country, and if that same pilgrimage requires the use of such aids [as the civil government], then those who take this away from people deprive them of their own humanity.

CALVIN, INSTITUTES, 4.20.2

Sin has made us exiles from our true home. We are refugees from the Garden. But Christ, who made pilgrimage from heaven to earth for us (Phil. 2:5-11), guides us by his Word and Spirit, in the company of our fellow travelers, toward the New Jerusalem.